Manners of departure

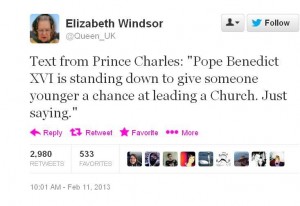

One wag on Twitter suggested that Prince Charles would have been avidly tuned in to the rolling news coverage of the shock resignation of Pope Benedict XVI – and indeed would have phoned the Queen to ask: “Have you got the telly on mother?”. But is the papacy a monarchical vocation? And if it is, ought it to be? Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI, in the contrasting manners of their departure, have offered illuminating answers to those questions.

One wag on Twitter suggested that Prince Charles would have been avidly tuned in to the rolling news coverage of the shock resignation of Pope Benedict XVI – and indeed would have phoned the Queen to ask: “Have you got the telly on mother?”. But is the papacy a monarchical vocation? And if it is, ought it to be? Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI, in the contrasting manners of their departure, have offered illuminating answers to those questions.

Benedict’s resignation – the first for almost 600 years – highlights how for centuries the Church has been chary of papal resignations. A living ex-Pope can present his successor with a big problem. The old pope stands, however silently, as a potential rallying point for nostalgic discontent; the new pope may spend much of his time looking over his shoulder. The modern media age adds another problem. At the first sign of papal ill health an avalanche speculation and questioning will begin which could be unnecessarily unsettling.

None of that explains why Pope John Paul II struggled on in office for years despite a courageous fight with Parkinson’s Disease which meant that eventually he was unable to walk or speak normally. His public bearing of his evident suffering was central to his theology.

The man who had been a fine athlete before becoming Pope had preached much to the world about the intrinsic dignity of the human person. Each individual, being made in the image of God, is to be respected simply for their being. In a world where people are valued for what they do or own this was a radical reminder. It was at the core of his insistence on the protection of the vulnerable – the poor, the sick, the disabled, the unborn and those close to death. All have the same intrinsic value and personal dignity as any one else. To be, not to do, is enough to define a person.

Preach the Gospel always, St Francis of Assisi is supposed to have said, and if necessary use words. John Paul’s drawn-out dying was part of his witness to the world. There was nothing romantic about it. Suffering is an evil and a trial in itself, he wrote in Evangelium Vitae, but it can always become a source of good. Not to comprehend that is to disregard God and over-estimate human autonomy – one of the besetting arrogances of our age. “Gradually, as the individual takes up his cross,” he wrote elsewhere, “spiritually uniting himself to the cross of Christ, the salvific meaning of suffering is revealed”.

But in doing that the burden of Pope John Paul II’s duties as pontiff fell on others, many of them on the man who would be his successor. That may well have been a key factor in bringing Benedict to his decision to resign. A man whose life has been utterly disciplined, internally and externally, may also have been able to reconcile himself to staying in office physically and symbolically but abdicating control of the Church.

“I am well aware that this ministry, due to its essential spiritual nature, must be carried out not only with words and deeds, but no less with prayer and suffering,” he told fellow cardinals – before adding the key judgement: “However, in today’s world, subject to so many rapid changes and shaken by questions of deep relevance for the life of faith … both strength of mind and body are necessary”.

Such logic is, an one Italian commentator has put it, “an eruption of modernity inside the Church”. If so there is a deep irony in so conservative a pontiff – who restored the Latin mass and set up an Anglican ordinariate, quashed collegiality and promoted reactionaries as bishops, and slapped down US nuns as he had liberation theologians – should have departed by doing something so thoroughly modern.

Follow

Follow

Comments are closed.