Something else that’s wrong with the British press

How do you write about poverty an indifferent world? The week of the Leveson report is not a bad time to step off the treadmill of the news agenda to ask a few questions about the values which underlie the way we look at the world. The stimulus for me was a request to take part in a seminar at the Frontline Club on news values and the developing world. But the lessons it offers have a wider application.

How do you write about poverty an indifferent world? The week of the Leveson report is not a bad time to step off the treadmill of the news agenda to ask a few questions about the values which underlie the way we look at the world. The stimulus for me was a request to take part in a seminar at the Frontline Club on news values and the developing world. But the lessons it offers have a wider application.

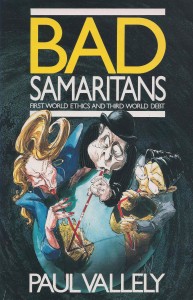

The shock of encountering the reality of poverty in famine-struck Ethiopia in 1985 changed my perspective on life. As I moved from one African country to another the common factors quickly made me realise that the problem was not just the weather and bad government but the relationship between the rich and poor worlds which was systemically structured to keep us rich, or make us even richer, and keep them poor. Naively, I thought that if only the iniquity of that system was exposed and explained then public indignation would compel change.

Nearly three decades on I understand that the politics of poverty is different, and that the media is in many ways part of the problem. News values focus on events rather than situations, symptoms rather than causes. The insatiable thirst for novelty gives journalists a short attention span. “We did starving people last week; what’s new? Let’s do how the aid goes astray, corrupt governments, nasty dictators and all the rest”. But there is more to this than an institutional attention deficit syndrome.

Bob Geldof has talked about “the pornography of poverty”. It’s an apt phrase because so much coverage of disasters focuses on sensation rather than relationships. It requires ever more novel, or extreme, examples to be deemed worthy of space or airtime. And it portrays those who suffer as victims over whom we stand in a relationship of power, often disguised as pity.

Aid agencies try to guard against this by insisting on positive images in the photographs used to publicise their work. But news editors – and indeed agencies’ own fundraisers – have little truck with that. An additional problem is that news editing is such a high-pressure job that it has a very fast turn-over, meaning that the gatekeepers to what gets in our newspapers need constantly re-educating out of the ignorant understanding of aid they share with most of the population.

Ignorant is not a kind word. It implies not just lack of knowledge but a lack of care. But that is what subconsciously underlies the chic cynicism of the constant stream of snide sniping about corruption and failed aid projects. Of course there are failures, but the substantial majority of aid succeeds in alleviating poverty or promoting economic development. This knocking copy shows more than indifference; it reveals a resistance, or even hostility, rooted in a subliminal urge to financially, psychologically and emotionally maintain and justify the status quo. Insightful journalism can challenge that. But it is no easy task getting space to write it.

That is why, in the end, journalism alone cannot deliver. It is why I became embraced more direct activism, working with aid agencies like Christian Aid, Cafod and Traidcraft, and becoming involved with Bob Geldof and Bono in the Commission for Africa, Live 8 and Make Poverty History, lobbying G8 governments on debt and aid debt relief at Gleneagles.

Not all the promises made there were delivered and world leaders have failed utterly on trade reform. But as a result of what was done at Gleneagles 40 million more children are in school, six million people with HIV or Aids are on life-saving drugs, malaria has been halved in eight countries and 1,700 fewer children die every day from preventable diseases. Journalism alone could not have delivered that.

The Church Times

Follow

Follow

Comments are closed.