A week in the life of a family on the edge of starvation

It would not be dawn for a little while but the ox was stirring in the corner of the room. It turned its head and its warm breath fell softly on the bodies of the two boys huddled in an old grey blanket by the side of their father. Gebremariam Goytem coughed and entered those moments of half-consciousness before the start of a new day. Lying in the darkness he heard the plop of the ox defecating on the floor of the bedroom. The smell mingled mellow with the warmth of his sons’ breath and the body heat of the animal.

Outside the air was cold and the flies were not yet awake. The first hints of the new morning appeared above the horizon opposite. Across the vast landscape of sand and blood-red rock a tiny figure in white robes was making slow traverse. It was one of the village’s many priests, making his way to the church to begin the daily prayers for rain but for that moment, it seemed, he could have been Christ returning from his 40 day isolation in the Palestinian wilderness.

The first birds were heard and Gebremariam swung his legs over the side of the bed. Its wooden frame, lashed together and strung with rough rope, creaked as he rose. He did not need to dress; like all his family he only had one set of clothes which he rarely took off. He had worn them for more than two years. The drought was now so severe that there was no water to wash them; in any case, as his wife Letenk’iel wryly observed, washing only wore out clothes more quickly. He stood in the doorway and stretched. By his feet a black-headed sparrow was pecking in the dirt for grubs.

Noises began to be heard from behind the other door of the house. The rooms were not linked. Both opened independently onto the dusty little yard which was flanked on one side by an empty stable and on the other sides by dry-stone walls overlooking the wide plain of rocky fields. Behind the house a long mountain loomed; against the lightening sky it looked like the fossilised spine of some gigantic prehistoric beast.

Noises began to be heard from behind the other door of the house. The rooms were not linked. Both opened independently onto the dusty little yard which was flanked on one side by an empty stable and on the other sides by dry-stone walls overlooking the wide plain of rocky fields. Behind the house a long mountain loomed; against the lightening sky it looked like the fossilised spine of some gigantic prehistoric beast.

The second door opened and Letenk’iel stepped out blinking in the first light. The sparrow had been joined by a second. Everytime the bird found something edible it hopped across and, instead of swallowing it, transferred the titbit into the mouth of its companion and then cleaned its beak on a twig. Letenk’iel went back inside and sprinkled water from a squat earthenware jar across the mud floor of the room.

From the first room the two boys emerged. The eldest Daniel, aged 13 but the size of an eight year old, drove the ox out to the stable. His younger brother, Kudos, aged 10, picked up an old metal ammunition tin. It had been abandoned by the Ethiopian army which had once occupied Meshal, their little highland village, before being ousted by the rebels of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Army who were seeking to restore the independence of the former Italian colony, forcibly annexed by the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie in 1962. Kudos filled the tin with dust which he mixed with the ox dung to dry it before scooping it into the tin and taking it outside to the store of dung to be used to fuel the fire.

From the second room the first of the girls Mabraheet, aged 8, appeared to find a brush of long grasses bound tightly together. It lay against the outside wall. Taking it inside she brushed the earthen platforms which surrounded the three sides of the room and acted as seats. She omitted the wider one which served as the bed of her mother, her sisters and the younger children. Then she brushed the dampened floor. The youngsters watched from amid the goatskin and two blankets which constituted the entire bedding. Azmera, her six year old sister, lay on her tummy and yawned. “You’ve missed a bit,” she said, cheekily.

Their little brother Teklom, aged 2, snuggled down beside the baby Habtom. He was not yet awake and had not therefore been overcome by the jealousy of the baby which dominated his waking hours. The day before Teklom had announced – as he did most days – that tonight he would sleep with the men. But when night had fallen he changed his mind as usual and remained with his mother and the girls. Gebremariam poked about in the straw where the hens had spent the night in the hope that there might be eggs. He had hoped there would be a few to take to market to exchange for salt and oil. But there were none.

The baby began to cry. Perhaps Teklom, unsupervised, had nipped him again. Letenk’iel issued her morning instructions. Mabraheet fastened the baby to her back with a long dirty cloth to keep him comforted until his mother had the time to breast-feed. Kudos went across to the stove to rescue the smouldering brand which had been carefully placed in the ashes the night before; matches cost 1.25 birr a box (almost 18 pence) and were too expensive for the Goytem family to afford. Daniel went in search of slow-burning wood to place in the biscuit-tin style stove to roast the kernels of food-aid wheat for that morning’s breakfast.

Letenk’iel distributed a handful to everyone. The monthly distribution of food-aid was overdue by a week. To make matters worse the last distribution, plagued by problems of transportation, had given everyone only two-thirds of the individualration of 15 kilos of wheat. The food supply was almost exhausted.

“It is two years since we had even a small harvest,” explained Gebremariam. “We spread it out as long as we could but it went long ago. Last year we ploughed and planted but we got nothing so we had to sell all our sheep – 20 of them – and our ox to buy grain. The ox we have has been borrowed from my uncle. All we have now is one hen with six chicks. “We are very poor now and we depend completely on food-aid. We can have only two meals a day. Because it is a holy day we are having breakfast but often we have no breakfast. Today we will have no lunch.”

All Saturdays are holy days. The Coptic Church, retaining as it does many Hebraic characteristics in its Christianity, conjoins both Saturday and Sunday into an extended Sabbath and outlaws work on both days. That meant there could be no ploughing. But there was plenty else to do. The Goytem family sat around and discussed their day. Gebremariam would inspect his fields to see where ploughing should begin if he was able to borrow a second ox from someone for Monday. Letenk’iel would perform the usual round of chores of fetching water, preparing food and cleaning the house. Kudos would take the ox on the long trek for water. Mabraheet and Azmera would fetch firewood from the mountain, a round trip of four hours. And Daniel would take his grandfather’s donkey down to the food distribution point – wheat was being given out to another village that day – to see if he could hire the beast out to a family needing to carry their rations to a distant village. There was a lot to do, considering that this was a day of rest.

Across the plain the groups of ghostly figures glided silently towards the church, their coarse white robes pulled tight around their heads against the chill of the cold mountain dawn. The thin white wrappings gave them the eerie look of mummies or the shrouded occupants of graveyards, fresh risen from their burial places on the Day of Resurrection.

The bell of the church, rusted brown and shaped like a gong, had long since ceased to ring. The call to prayer had been at midnight, an hour before the long nocturnal service had begun. It was 6am but there was still another two hours of the ancient liturgy to be completed. Only the priests and the truly devout had been there from the beginning.

Gebremariam was one of them, though he did not enter the church. Because of the shortage of water he had not been able to find enough to bathe properly and make himself ritually clean.

He remained, therefore, by the door of the church. From there he could hear the long litanies and antiphonal chantings of the priests inside and bow before them as their procession left and re-entered the church in a colourful swirl of vestments, copes and parasols. From there he was able to smell the heady incense and kiss the bible, written in ancient Ge’ez, a language which has been dead longer even than Latin, when it was brought to the door. As the light grew it revealed the vague shapes of figures praying outside the church wall. Inside the compound others leaned against the plinth on which the church of the Archangel Mika’el stood. It was a square building of two tiers, the second much smaller than the other, perched like a squat tower in the centre of the square, as if to reflect the concentric design of the interior. At its heart lay the sanctuary in which stood the Holy of Holies, a tabernacle of battered green-painted metal separated from the faithful by a thin cotton sheet, worn now almost to translucence.

Behind the church the vertical strata of the mountain rose like some gigantic organ. The positions of the worshippers indicated their degree of cleanliness: the men who were fully washed and untainted by recent sexual intercourse could be found inside the church, beside the very sanctuary; those women and men who were less clean were outside the door or further off at the bottom of the plinth; the unwashed or menstruating women worshipped from actually outside the churchyard. The walls of the building were only of mud painted in pink and yellow and its roof was of corrugated iron painted a pale green. But it was by relation to the little stone huts which were scattered across the hillside, the most handsome building in the landscape. It towered across the stony plateau before it to the glory of God, much as the spire of Salisbury Cathedral must have done for the peasants who trudged across the plain to its medieval markets. But the church of the Archangel Mika’el, or its predecessor, had stood against the mountain long before a stone had been raised at Salisbury, York or Canterbury.

The Christian faith was brought to these highlands in the 4th century where – protected in its mountain fastness from the schisms, reformations, inquisitions and modernisations of the Western church – it has been preserved its original forms.

The long service was conducted almost entirely in Ge’ez. Only at one point did the congregations lapse into their demotic tongue, Tigrinya. One of the five celebrants had left the Holy of Holies and moved among the congregation ringing a bell continuously and wailing a long and mordant chant. The men and women of Meshal responded with the repeated intercession: “Forgive us all our sins, O Christ”. As

they cried the women moved their hands rhythmically up and down in the same gesture which the destitute beggarwoman used when begging for bread through the village the day before. The prayer was for rain.

After the service was over the congregation moved to a long low barn-like building in the corner of the churchyard. There the priests were sharing with the people the food which had been brought as offerings for the liturgy. In good times this can be a veritable feast but in a time of hardship there is only the local flat soured bread to be divided amongst the faithful.

The fare was only slightly better at a party to which Gebremariam and his wife were invited later that morning. It was a strange and moving gathering – half social, half religious – which a group of 12 men and women took it in turns to host each Sunday. This week the hostess was a widow. She had prepared for her friends made from fermented sorghum, and a high quality form of the local bread. Her husband had died in the 1984/5 famine and she and her two children found things difficult, even though they owned their own ox. The sewa was poured into enamel goblets with drawings of angels on the side. The widow filled them to the brim – anything less would be considered a reluctant offering. The bread was passed to Gebremariam for the blessing. He broke and distributed it. It was dark and strong, the texture of gingerbread.

The children had been excluded so conversation centred at first on the only child present, a baby with big ears who sat in the centre of the mud floor with a piece of bread and some diluted sewa. He dipped the bread into the drink, prompting general merriment.

“He’s got your ears, Tsehaye,” one woman said to the baby’s father who laughed with embarrassment. A general hubbub of conversation developed.

“Did the people of Menokseto get their food distribution yesterday?”

“Yes.”

“Is there any news when we get ours?”

“No.”

“How come they got their’s first?”

“They’re in a bad way. People are dying there. Things were so bad that three families arrived at the distribution point the day before, including a blind man who had walked for eight hours, to say that they couldn’t wait for even another day for food.”

In one corner an old man, known as the storyteller embarked on a long tale. “There is a story. Once there was a man who often complained of the laziness of his children. Very well, said his friend, let us have a test. Tomorrow you will come to my house and act in all of the things which are proper to a child and perform all the tasks which are required of him…”

The widow offered more sewa. In normal times people would take four or five cups and the talk would spin on into the afternoon. But that day everyone pretended that they had had enough after one helping. They knew she would not have enough to go around a second time. After only an hour everyone took their leave, with Letenk’iel swearing an oath over the sewa that, with the help of God, she would take her turn to provide food and drink for her friends next week. On the steep path up the side of the hill back to their home Gebremariam told Letenk’iel that he had done a deal. He could have the widow’s ox to plough his land and in return he would plough hers afterwards. He would be able to begin tomorrow.

MONDAY

Gebremariam has two tsemdi of land on different parts of the plateau. He cultivates each in turn, leaving the other fallow for a year. A tsemdi is the amount which one man with two oxen can plough in a day, though because there had been no rain Gebremariam said it would take him longer than a day to plough each. His field lay at the eastern end of the mountain, where in a massive outcrop it met

the plateau just before both plunged in an awesome sheer drop more than 1,000 feet in to a deep ravine below.

In ancient times, the villagers told their children, the Archangel Mika’el had promised their ancestors that he would bind the giant outcrop with invisible ropes so that not a single stone would fall from it. The rock was pure in its stratification; elsewhere its structure was obscured by vast slopes of scree where, not bound by the angelic undertaking, the rocks had for centuries shattered and scattered themselves down its steep slope and onto the fields below. The rocks were everywhere. There was not a square foot of soil which did not contain four or five sizeable examples. The larger ones had been removed to build terraces to stop the precious soil eroding into the valley below. But the rest remained where they lay.

“There is no point moving them. The plough would just turn up others in their place,” the peasant farmer said.

He had risen early and as soon as there was enough light in the sky to warm the muscles of the oxen he and the boys had set out for the field. Only the oxen had eaten breakfast. They had been given a little of the straw from last year’s unripened harvest, stored in a small stack behind the house, as fodder for such special occasions.

“Look after the donkey, Azmera,” shouted Daniel as they left.

“Why should I?” shouted Azmera, contrary as ever.

Daniel had borrowed the beast from his grandfather on Saturday night to carry food from the distribution. He had left home at 11pm when the moon rose and walked with the donkey through the night for six hours carrying the sacks of grain. It had been a six hour walk back. He had arrived home in the middle of Sunday with his fee – six birr (88 pence), enough to buy about a pound of sugar. They would not be expected to return the beast immediately and could keep it for fetching water that day.

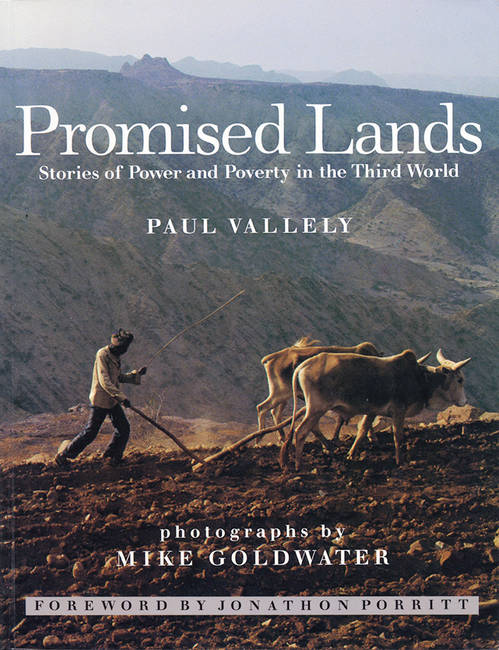

The oxen were yoked in the field. Their names were Senaye and Berhane; Good News and Light – though they were cajoled with epithets such as “Smelly Beast” as the arduous ploughing got underway. As Gebremariam shouted to the beasts his voice rebounded in a pure echo from the archangel’s rock. It was hard work. Often he walked at an angle of 45 degrees in order to put the force of his whole body behind the single, spiked ploughshare. Daniel and Kudos began moving the larger rocks and using them to staunch the terraces and the canals built at the edges of the field to hold the flood water if it did rain. Azmera appeared herding the donkey to a little scrubby pasture nearby where she abandoned it with an insolent glance at Daniel. She was followed by Mabraheet, baby on back, collecting bits of dead cactus for kindling. The ploughing continued. By 8am the sun was already high in the sky and the work was hot. Azmera reappeared with an old towel containing a few handfuls of roasted wheat.

She poked around in the newly ploughed soil for edible seeds as the workers ate their breakfast looking down on the deep Moror valley below. “It was all wooded with wild olives once,” said Gebremariam. “Then the Ethiopian army came and took all the wood for their trenches. We terraced it afterwards and planted eucalyptus tree but they all died in the drought last year.”

Taking turns at ploughing and terracing the man and boys worked until just before noon when the heat became too much. Late in the afternoon the skies darkened and in the distance rain clouds loomed. They lingered for three hours but failed to deliver.

TUESDAY

It was Baele Egzi’abhr, the Day of God, another holy day when therecould be no work in the fields. There is a prodigious number of festivals in the Abyssinian Church. Each month has ten feast days to commemorate the various archangels, Ethiopian saints, as well as days dedicated to the Father, the Son and to the Trinity (Haile Selassie is literally a translation of Holy Trinity). Of the 10 monthly days of religious observance no work is permitted on four of them, in addition to the eight Sabbath days each month.

To judge by the weakness of the oxen at the end of yesterday it was perhaps as well. Another day’s ploughing might have done for them. But the dozens of non-farming chores had to be performed. For his share Kudos was to take the oxen to drink. As he left other boys joined him with their animals. Villagers came out and asked if they would take other oxen too. The herd swelled, though they turned down all requests to take donkeys. “The place is not suitable for them,” said Kudos. We were to find out why.

It took more than an hour to reach the water hole, situated in a dried out river bed at the bottom of what was once clearly a waterfall. On the way the boy passed six dams all constructed that year by the villagers in the hope of conserving what little rain fell. Each was now dry. The water was in the seventh, where a dam had been built just beyond the fall and the pool at the base dug out to deepen it. Further downstream stood an eighth dam. “We began it but we didn’t have the strength to finish it,” said on old man who stood by the pool, gazing listlessly down. “There’s about six weeks’ water left. After that the animals will start to go.”

There was a steep path down to the murky brown waters which were the colour of milky coffee. The crowds of children stood with their animals and waited their turn. Finally Kudos took down his charges. The beasts walked gingerly to the muddied edge of the pool. They seemed to drink surprisingly little. Suddenly, without any warning beyond a horrified shout from one of the cowherds, Kudos’ principal ox took one step too far. It fell into the pool and began to swim desperately round in circles. One of the elder boys rushed to the edge and began to wave a stick at the animal, directing it to the easiest egress. The beast swam in circles for almost five minutes before finally clambering exhausted into the mud at the edge.

“Now you can see why we don’t bring donkeys,” said Kudos, after pelting the hapless beast with rocks to recover his composure. “They can’t swim and drown straight away. I was scared the ox was going to drown. He was starting to slow down. If he had got tired he would have stopped and then just drowned. What would my dad have said?” It was not Kudos’s day. His name in Tigrinya means, ‘ The Blessed,’ but that day he seemed to be The Jinxed. When he got home he was told to stable the donkey. As his mother and father sat inside the house discussing the possible dates for the next food distribution, there was sudden commotion outside. The donkey had collapsed. Gebremariam rushed out.

“What happened?”

“I just hit him, and he fell over.”

“Where”

“On the neck.”

“You stupid boy. Hit on the rump, never on the neck. Spit on the blow. Spit on it”

In the highlands spitting is the etiquette for withdrawing an insult or blow. The boy laughed nervously. His father fetched him a great wallop around the ear. Kudos began simultaneously to cry and to spit. Gebremariam rushed inside.

“The ashes of Abune Aregawe… quick.”

Letenk’iel snatched a small bottle hanging by the door. It contained the ashes of some holy relic blessed by a priest at the shrine of Aregawe, an Ethiopian saint who had been lifted up to God in the tail of a dragon. She sprinkled a little in basin and filled it with water. Gebremariam took it out for the famished donkey to drink.

“I didn’t hit him very hard,” said Kudos. “It was only a tap. He’s just weak from hunger.”

The animal stood up.

“Abune Aregawe has saved him. God is with us,” said his father.

WEDNESDAY

Her husband and sons were ploughing the widow’s field. Letenk’iel had swept the house and rekindled the bigger stove in the little kitchen opposite the stable. It was time to breastfeed the baby. Often this took a long time. Her milk did not flow as freely as it might, largely because when there was no much food to go around she took hers last and sometimes did not bother at all. She coughed – the sound was loose and rattling – as she prepared a few little tasks which could be done as the four-month-old suckled. Into a large flat pan she poured the last of the food-aid wheat kernels. There was about half a kilo there which she shook over the flames of the little portable stove she used to cook inside the house.

The big stove was largely restricted for making the flat kitcha bread pancakes which was the staple diet locally at times when wheat was plentiful and there was money to pay the miller to grind it.

She had a little flour left, she knew, from her husband’s visit to the miller who charged five birr to grind 50 kilos of wheat. But that was to be saved for the holy days. The money which Daniel had earned would buy them a kilo and a half of food-aid wheat from the market traders. She could stretch that for three days. Perhaps the new food-aid would arrive by then. She cleaned her teeth as she thought, chewing on a twig of olive wood which is the traditional toothbrush in the highlands. It was an hour before the child had taken his fill. When his eyes closed she passed him over to Mabraheet who lay him among the blankets on the bed. The donkey had been returned to its owner now and the water had to be fetched by hand. She lifted the large plastic jerrycan from beside the unglazed earthenware jar which kept the drinking water cool to set off for the pump. But before she could leave the two-year-old was at her side.

“Habtom has been biting me.”

“Habtom hasn’t got any teeth. He’s only a baby.”

“Well he’s got four teeth now. And he’s scratching me as well.”

“Go back and help Azmera collect the donkey dung for the fire,

or else you’ll have to walk to the pump with me.”

It was a 25 minute walk down to the pump but it would take 40 minutes to walk back up the hill with 5 gallons of water wedged into the small of her back and tied on with a rope of old rag. On the way down she met a neighbour also bound for the pump.

“How’s the woman next door?”

“She’s still sick…”

As they passed the church the women stopped to kiss the wall of the sacred building and touch their foreheads upon it before resuming their conversation.

“… but she’s got her children to look after her, fortunately.”

“Tell her to give a shout if she needs a hand with anything.”

At the pump the queue of people was long and the flow of water had reduced to a trickle from the two-handled pump which bore the logo: Mono Pumps Ltd, Manchester.

“It’s not getting any better,” complained Demekesh Giday, the woman who was paid by the villagers to be the guardian of the water to ensure that none was wasted. She was supposed to be paid 50 cents (about 7 pence) a year by each family for her day-long task, seven days a week. These days no-one could afford to pay her but she worked on. Once there were three wells. The eight metre well has dried up entirely. The nine metre well has a little brackish water at the bottom which even the donkeys wouldn’t drink. The flow from the pump of the 25 metre well had slowed to a painful trickle. In Meshal there was no question of watering vegetable plots. There was not even enough for people to bathe. Rather there was just barely enough for everyone to drink. Small wonder that skin ailments were a common sight. Letenk’iel hoisted the five gallon container into the air and swivelled it round to lodge in the small of her back. Her friend fastened it in place. When she reached home the tops of her legs and lower part of her back ached but Gebremariam was back and, without pause, she began the preparation for lunch.

It was noon. There had been no breakfast for her husband that day for every Wednesday, like every Friday, was a fast day. Nothing could be taken before noon, not even a drink of water and throughout the day no products associated with the blood of a living creature – meat, eggs, or dairy products – could be eaten. The notion was a formality to Gebremariam. There were no such foods in his house, nor had there been for some months. If the hens laid eggs they were taken to market to barter for oil and salt. Lunch was the roast wheat which she tipped into a basket and passed around. Azmera, uncharacteristically serious after her morning collecting fuel, let the basket pass. Her mother questioned her.

“Are you not well?”

“I’m OK. I’m not hungry. Let the boys eat. They have been working.”

“You eat too.”

The six-year-old turned and left the room. A woman’s responsibilities are thrust early upon the young girls of the highlands. When the heat had gone from the sun Gebremariam took the six birr his son had earned and set out for the market at Sena’afe. It would be a seven hour round journey to buy tomorrow’s food.

THURSDAY

It was Baele Mariam, the Feast of the Virgin Mary. It was not her monthly feast but one of the 33 annual commemorations which mark out Mary’s quasi-divine status in the Ethiopian cult. On holy days the morning begins with coffee. Letenk’iel roasted a tiny handful of green coffee-beans in a small blackened pan over the little stove. They had cost one birr (15 pence). Coffee is not regarded as a luxury but as a necessity by these highland people. Gebremariam had bought enough coffee for holy days by selling some of the wheat the family had been given in the last food-aid distribution. But that had been more than a month ago and this was the last of the coffee, just as they were down to the last of the wheat. The beans were ground in an ancient wooden pestle, sterilized with a brand from the fire, and brewed in a tiny pot, no more than five inches high. The ritual performed by the woman of the house was long and elaborate. The coffee cups and the battered old enamel plate on which they stood were washed and rewashed. The coffee was brewed and rebrewed, with cold water poured down the narrow funnel everytime it threatened to boil over.

Finally the coffee was ready. The hairs of an ox tail were stuffed into the neck of the pot to filter out the grounds. Azmera, whose name in Tigrinya means, ‘Harvest,’ crossed to the woven cover under which their cooked bread was kept. She placed the single piece on a flat basket and took it to her father, waiting with a sense of ceremony as Kudos poured water from an old marmalade tin (ex Ethiopian army) over his father’s hands and let it fall into the ammunition tin placed below.

Gebremariam took the bread in his hands and blessed and broke it.

“Almighty God bless us, be with us, save us from all the dangers and bring us good things. Archangel Mika’el, please help us. Archangel Gebreal, please help us. Save my children. Protect them for all harm. You the Saviour, be with us today and always.”

At one time Gebremariam had hoped that Daniel might become a priest. He had sent him off to the local priests’ school but after two years had had to withdraw him because of lack of funds. “If it rains this year I hope he can return.”

A guest had arrived. Holy days are the time for visiting. Tsegay was an old friend of Gebremariam. He would be expect to stay for three pots of coffee, as tradition obliged. With a leisurely, well-spaced conversation, the whole proceedings could take three hours.

“How’s the market in Zelambessa?”

“Prices are fluctuating. The price for sheep is going down.

They’re all very skinny now. But goats are holding up.”

“How’s your donkey? Did he go with you?”

“He’s terrible. I left him with a friend. He wouldn’t have madethe journey.”

“How’s the grazing at your place?”

“Why should I worry? I only have one sheep left. I’ll leave the worrying about grazing to the rich.”

Letenk’iel had finished the coffee ceremony, at the latter part of which she had some too; there was none for the children as only those who are married are allowed to take coffee with their parents.

She rose and announced that she must make a visit too: to a friend whose 14-year-old son had drowned the week before in the ox pool. “His stick fell into the pool and he fell in stretching to reach for it,” she told Tsegay. “He couldn’t swim, of course, how could he have learned when there is no water around here?” Kudos giggled nervously and told the story of the ox. Gebremariam shook his head at his son’s latest recklessness.

FRIDAY

The dawn broke, reluctantly it seemed, revealing that the sky was overhung with a heavy haze of grey cloud. It did not promise rain but only a dull skyscape to match the mood of the morning. It had looked like this for almost a week now but still there was no rain. Terhas arrived home that day. Terhas was the eldest child of Gebremariam. She had been away for more than a week to take the holy waters at a sacred well to cure her of a spell of dizziness and fainting fits. Her father and brothers were in the fields ploughing again when she came back. Letenk’iel was sitting in the stable, picking the lice from Teklom’s jumper. She was relieved to see the 15-year-old.

“We thought you’d be back a couple of days ago.”

“It took longer than I thought. But I feel fine now.”

Terhas picked up her baby brother and held him in the air with hislegs wriggling. “Ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-mouche,” she chanted. Mamouche in Tigrinya means Baby Boy.

“Was there a distribution going on by the road?” asked hermother.

“Yes, but not for us. It was for Acran.”

Everyone in Meshal knew about Acran. There was a wild beggarwoman sitting by the path to the water pump who came from Acran. It was hunger which had made her demented. She wailed, as she begged, of the four old people, the four children and the woman she knew who had died from starvation. Reports from the officials of the indigenous aid agency, the Eritrean Relief Association (Era), confirmed the gist of the mad woman’s story.

“The people there look terrible,” said Terhas. “Their bodies are so thin. And those are the one who have walked (It was a six hour trek). What will the rest be like at home?”

“Was there enough in the store for a distribution for us?”

“The Era people said not. The road to the port has been closed by floods.”

“It’s a pity that none of the rain fell here.”

Letenk’iel caught sight of a new rip in Azmera’s thin and grimy little dress.

“How did that happen?”

“It wasn’t me,” said the pert little six-year-old. “It got old.”

Her mother wrapped the child in a blanket while she sewed the threadbare material using a strand pulled from the sack of a food-aid bag. At the gate appeared an ancient priest. His cross was of brass, not the usual silver. He carried a beggar’s bag before him.

“Alms for the love of God,” he cried, explaining that he had been wandering from his home in Tigre for more than six months now. Letenk’iel reached inside her tiny grain store and put a handful in the man’s bag. “We don’t have much. But we can’t watch others starve. Let us hope that the food comes soon.”

Overhead the sky glowered. But the rain did not come. Gebremariam returned from the fields. He permitted himself one quick look at the sky, as if a longer look might tempt ill fortune.

“Are you counting the stars?” teased his wife.

“The clouds are right. The winds are right. The ploughing is complete. Perhaps God will send the rain. We must place ourselves in his hands.”

from the Telegraph Sunday magazine

Follow

Follow

Comments are closed.